'My abuser's smirk said: 'We both know what I did, and I got away with it'.'

Debrief Daily

Manny Waks

7 September 2015

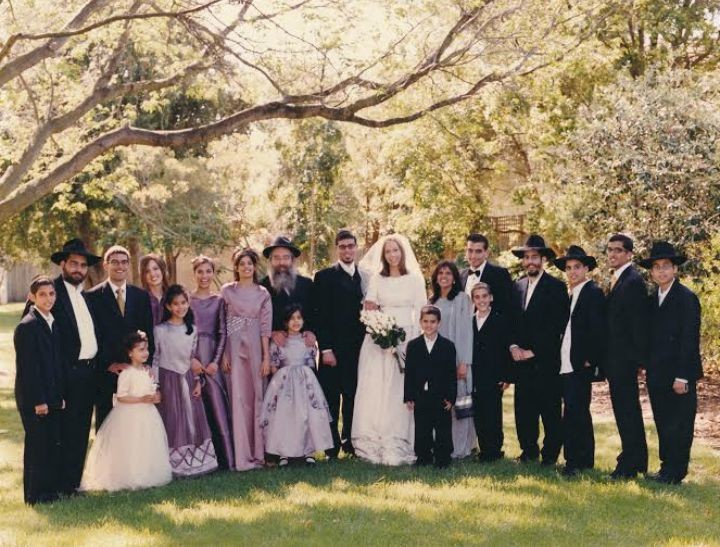

Manny, his new wife, his mother and father and all of his siblings on his wedding day 21 November 2000.

Manny, his new wife, his mother and father and all of his siblings on his wedding day 21 November 2000.

Trigger warning: This post is about child sexual abuse and may cause distress for some readers.

There were 17 of us siblings in our family – 11 boys and 6 girls, with no multiple births and all to the same parents.

The dynamics in the house were different to most families, and not only due to the fact that we were ultra-Orthodox Jews, belonging to the worldwide Chabad movement. Throughout most of my life, the Yeshivah Centre in Melbourne – located literally across the road from our home – was the centre of my Jewish family’s universe.

While there were many beautiful moments, often the home functioned like a large corporation or a military camp rather than a conventional family. Each older child was responsible for a younger sibling, ensuring they ate their breakfast, made their school lunch, did their homework. We even changed their nappies. The two siblings would share a room. As the second eldest, I was responsible for several of my siblings over the years. Moreover, as the eldest boy, I played a unique role in the family, commanding the special respect owed to an older brother.

There were 17 of us siblings in our family – 11 boys and 6 girls, with no multiple births and all to the same parents.

The dynamics in the house were different to most families, and not only due to the fact that we were ultra-Orthodox Jews, belonging to the worldwide Chabad movement. Throughout most of my life, the Yeshivah Centre in Melbourne – located literally across the road from our home – was the centre of my Jewish family’s universe.

While there were many beautiful moments, often the home functioned like a large corporation or a military camp rather than a conventional family. Each older child was responsible for a younger sibling, ensuring they ate their breakfast, made their school lunch, did their homework. We even changed their nappies. The two siblings would share a room. As the second eldest, I was responsible for several of my siblings over the years. Moreover, as the eldest boy, I played a unique role in the family, commanding the special respect owed to an older brother.

Manny in his first year of high school.

Manny in his first year of high school.

Despite the militaristic discipline, it was a wonderful childhood within the home. We had no television, but watched family videos, ‘kosher’ documentaries and religious films. There were no novels lying around. We read only religious texts or stories.

Every aspect of daily life was dictated by religion. For example, it was compulsory to put on the right side of our clothing before the left, recite at least 100 blessings a day, pray three times daily and wear particular garments. We were encouraged to spit while walking past a church. Astonishingly, I was unable to distinguish between Jesus and Hitler; until well into my teenage years I had believed they were different names for the same wicked leader.

On weekends and on school holidays we would go for day trips and overnight stays. We hosted guests, for Sabbath meals and on many other occasions. Often guests would sleep over.

Every aspect of daily life was dictated by religion. For example, it was compulsory to put on the right side of our clothing before the left, recite at least 100 blessings a day, pray three times daily and wear particular garments. We were encouraged to spit while walking past a church. Astonishingly, I was unable to distinguish between Jesus and Hitler; until well into my teenage years I had believed they were different names for the same wicked leader.

On weekends and on school holidays we would go for day trips and overnight stays. We hosted guests, for Sabbath meals and on many other occasions. Often guests would sleep over.

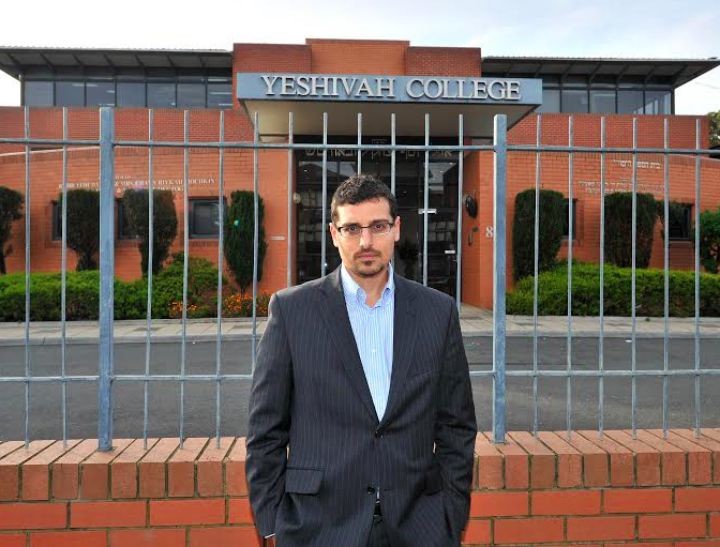

Manny stands outside the Yeshivah College where he was sexually abused as a child. Image: News Limited.

Manny stands outside the Yeshivah College where he was sexually abused as a child. Image: News Limited.

Then there was my life outside the home.

From the age of 11, I was groomed for sex by an adult perpetrator at the Yeshivah Centre.

I was offered attention and special treats, including the opportunity to drive a car on the grounds of Yeshivah. The perpetrator, Velvel (Zev) Serebryanski, the son of one of Australia’s most prominent Chabad leaders, sexually abused me for the first time inside the Yeshivah synagogue during the festival of Shavuot, when it is customary for men to remain awake all night to undertake religious studies. I went upstairs to the women’s section of the synagogue to rest on one of the wooden benches. Serebryanski followed me up there, sat on the bench beside me and started stroking my clothes, initially on my thighs and eventually my groin area. He undid my belt and unzipped my trousers and felt around my penis and groin over the top of my underpants with his hand.

After a short time he stopped and said something like “This isn’t for a place of worship, let’s go outside”. He then led me to the adjoining bathrooms where he continued to molest me. To this day I am unsure why I followed him.

Serebryanski abused me in a similar way on at least two other occasions, both times on the Sabbath at another synagogue that we both attended.

From the age of 11, I was groomed for sex by an adult perpetrator at the Yeshivah Centre.

I was offered attention and special treats, including the opportunity to drive a car on the grounds of Yeshivah. The perpetrator, Velvel (Zev) Serebryanski, the son of one of Australia’s most prominent Chabad leaders, sexually abused me for the first time inside the Yeshivah synagogue during the festival of Shavuot, when it is customary for men to remain awake all night to undertake religious studies. I went upstairs to the women’s section of the synagogue to rest on one of the wooden benches. Serebryanski followed me up there, sat on the bench beside me and started stroking my clothes, initially on my thighs and eventually my groin area. He undid my belt and unzipped my trousers and felt around my penis and groin over the top of my underpants with his hand.

After a short time he stopped and said something like “This isn’t for a place of worship, let’s go outside”. He then led me to the adjoining bathrooms where he continued to molest me. To this day I am unsure why I followed him.

Serebryanski abused me in a similar way on at least two other occasions, both times on the Sabbath at another synagogue that we both attended.

Manny testifying at the Royal Commission into his abuse.

Manny testifying at the Royal Commission into his abuse.

In 1988, when I was 12 years old and after yet another grooming process, I was repeatedly molested by David Cyprys. Cyprys, an ultra-Orthodox Jew and a well-known member of the Yeshivah community, was responsible for security at Yeshivah. He was also our karate teacher. He was a figure many teenage boys, including me, admired and feared.

Cyprys abused me repeatedly during the karate classes, in his car and even in the male Mikveh, the ritual bathing house. The Mikveh is a sacred place, a place of purification. It is traditional within the global Chabad movement, as well as other ultra-Orthodox groups, for males from a young age to immerse themselves daily in the Mikveh.

At the time I did not feel there was anything I could do. Having been bullied after disclosing the abuse by Serebryanski, I did not even consider sharing the abuse by Cyprys with anyone. And this time I felt that it was my fault. After all, why would two separate, well-known community members sexually abuse me? This time around the shame, guilt and pain was amplified. And again, despite never speaking of my abuse, it was clear to me that people around me were aware of the sexual abuse occurring. I was frequently on the receiving end of casual and callous comments about Cyprys and I spending time together.

Before the abuse I was a reasonably well-behaved son, brother, student and friend. At home I was the proud older brother to many siblings. I helped out a fair bit. I was happy and positive. While not necessarily a model student, I completed my work and did not have any particular behavioural issues.

Cyprys abused me repeatedly during the karate classes, in his car and even in the male Mikveh, the ritual bathing house. The Mikveh is a sacred place, a place of purification. It is traditional within the global Chabad movement, as well as other ultra-Orthodox groups, for males from a young age to immerse themselves daily in the Mikveh.

At the time I did not feel there was anything I could do. Having been bullied after disclosing the abuse by Serebryanski, I did not even consider sharing the abuse by Cyprys with anyone. And this time I felt that it was my fault. After all, why would two separate, well-known community members sexually abuse me? This time around the shame, guilt and pain was amplified. And again, despite never speaking of my abuse, it was clear to me that people around me were aware of the sexual abuse occurring. I was frequently on the receiving end of casual and callous comments about Cyprys and I spending time together.

Before the abuse I was a reasonably well-behaved son, brother, student and friend. At home I was the proud older brother to many siblings. I helped out a fair bit. I was happy and positive. While not necessarily a model student, I completed my work and did not have any particular behavioural issues.

Manny (left) as a member of the Israel Defence Forces (1996).

Manny (left) as a member of the Israel Defence Forces (1996).

This all changed after the abuse; my world seemed to have collapsed. I felt alone, as though I had to fend for myself.

In school, my behaviour deteriorated, especially during religious studies, which invariably resulted in confrontations with, and alienation from, my parents, teachers and friends. Perhaps it was subconscious, but the teacher for whom I caused greatest grief was the father of my first abuser, Serebryanski.

I came to loathe religion, its practices and leaders, doubtless due to the abuse that occurred within a religious institutional environment. At the time of my Bar Mitzvah (at the age of 13), one of the most important milestones for a Jewish boy, I felt lost in the only world I knew. It is very hard to explain the depth of this despair, given my connection to this faith and this community. I was questioning my very existence. In my mid-teens, I would be expelled from two Australian ultra-Orthodox institutions.

At home, I became a very disobedient child. I regularly committed some of the gravest sins against our tradition – I desecrated the Sabbath, I ate non-kosher food, I didn’t pray, I didn’t fast. By the age of 14 I was also regularly consuming large quantities of alcohol, planting the seeds for a long-term substance abuse problem.

My parents dealt with my rebellion brutally, my father running the house less like a parent and more like a military commander. Receiving a belt was a common occurrence, especially to me, as the oldest boy and chief trouble-maker. I was even kicked out of home twice. In many ways I was a guinea pig in my parents’ experiment of determining how to respond to such disobedience.

In school, my behaviour deteriorated, especially during religious studies, which invariably resulted in confrontations with, and alienation from, my parents, teachers and friends. Perhaps it was subconscious, but the teacher for whom I caused greatest grief was the father of my first abuser, Serebryanski.

I came to loathe religion, its practices and leaders, doubtless due to the abuse that occurred within a religious institutional environment. At the time of my Bar Mitzvah (at the age of 13), one of the most important milestones for a Jewish boy, I felt lost in the only world I knew. It is very hard to explain the depth of this despair, given my connection to this faith and this community. I was questioning my very existence. In my mid-teens, I would be expelled from two Australian ultra-Orthodox institutions.

At home, I became a very disobedient child. I regularly committed some of the gravest sins against our tradition – I desecrated the Sabbath, I ate non-kosher food, I didn’t pray, I didn’t fast. By the age of 14 I was also regularly consuming large quantities of alcohol, planting the seeds for a long-term substance abuse problem.

My parents dealt with my rebellion brutally, my father running the house less like a parent and more like a military commander. Receiving a belt was a common occurrence, especially to me, as the oldest boy and chief trouble-maker. I was even kicked out of home twice. In many ways I was a guinea pig in my parents’ experiment of determining how to respond to such disobedience.

Manny & his father, Zephaniah Waks, testifying at the Victorian Government inquiry (2012). Photo: Tony Fink.

Manny & his father, Zephaniah Waks, testifying at the Victorian Government inquiry (2012). Photo: Tony Fink.

At the age of 18 I moved to Israel. This time away helped to crystallise my anger about the injustices of the abuse. I felt a strong shift in my focus, growing increasingly unable to live with the notion that this was happening to other children in the community.

In 1996, I returned to join my family in honour of my eldest sister’s wedding. The impact of the abuse was still very much alive, as was my desire to attain justice. While in Melbourne, I happened to hear on the radio of a police campaign targeting child sexual abuse. This prompted me to disclose the abuse to my dad. To his credit, he never doubted me, and called the police within minutes of my disclosure. For various legal and bureaucratic reasons the matters could not proceed.

At that time I also decided to confront the late Rabbi Yitzchok Groner, founder and long-term director of the Yeshivah Centre. It was made clear to me that Rabbi Groner was already aware of my abuse and that I was not to take any further action.

Having effectively been ignored by both the police and the most senior Yeshivah official, I returned to Israel, helpless and disillusioned.

In March 2000, I returned to Australia with my wife-to-be. As my parents still lived across the road from Yeshivah, often I would walk – alone or with my family, including my young children once they had arrived – past Yeshivah to get to my parents’ house. Most synagogues in Australia have security officers standing at the front of the synagogue. Astonishingly to me, Cyprys was often that security officer protecting the Yeshivah Centre. I recall many occasions when our eyes met as I passed. He seemed to deliberately smirk at me, fixing his eyes on me and continuing to smirk until I was forced to look away. To me his facial expression said: “We both know what I did, and I got away with it”. It infuriated me. It still does.

In 1996, I returned to join my family in honour of my eldest sister’s wedding. The impact of the abuse was still very much alive, as was my desire to attain justice. While in Melbourne, I happened to hear on the radio of a police campaign targeting child sexual abuse. This prompted me to disclose the abuse to my dad. To his credit, he never doubted me, and called the police within minutes of my disclosure. For various legal and bureaucratic reasons the matters could not proceed.

At that time I also decided to confront the late Rabbi Yitzchok Groner, founder and long-term director of the Yeshivah Centre. It was made clear to me that Rabbi Groner was already aware of my abuse and that I was not to take any further action.

Having effectively been ignored by both the police and the most senior Yeshivah official, I returned to Israel, helpless and disillusioned.

In March 2000, I returned to Australia with my wife-to-be. As my parents still lived across the road from Yeshivah, often I would walk – alone or with my family, including my young children once they had arrived – past Yeshivah to get to my parents’ house. Most synagogues in Australia have security officers standing at the front of the synagogue. Astonishingly to me, Cyprys was often that security officer protecting the Yeshivah Centre. I recall many occasions when our eyes met as I passed. He seemed to deliberately smirk at me, fixing his eyes on me and continuing to smirk until I was forced to look away. To me his facial expression said: “We both know what I did, and I got away with it”. It infuriated me. It still does.

Manny and the Groner family on the front page of Australian Jewish News (February 2015).

Manny and the Groner family on the front page of Australian Jewish News (February 2015).

Occasionally, for events such as a family Bar Mitzvah, I had to walk inside the Yeshivah Synagogue. Cyprys would be the security person standing there; he technically needed to authorise my entry. Moreover, since he was in charge of security, he had access to every room and facility on the premises. I could not believe that Yeshivah allowed him to remain in this position for so many years after I had discussed Cyprys’s actions with Rabbi Groner (in 1996 and again in the early 2000s). It has since been revealed thatsome within the Yeshivah leadership were aware of the allegations against Cyprys against multiple children as early as 1984.

From that point on, I became desperate to disclose my story publically. It took several years to arrive at the moment, largely because my wife and I wanted to protect our three children from the fallout of such a disclosure. However, on 8 July 2011, I shared my experience with the world.

Within months, consequences began unfolding at a phenomenal pace – the police were being inundated, investigations ensued, arrests were made. Simultaneously, my family and I were being attacked and ostracised by members of our own community.

It became clear to me that I could not address this issue alone, so the founding of a dedicated organisation in this area became crucial, especially as none existed. Towards the end of 2012 I established Tzedek, a support and advocacy group for Jewish victims of child sexual abuse. The major precursor to this was my written submission and public testimony before the Victoria Government Inquiry into the Handling of Child Abuse by Religious and Other Organisations.

From that point on, I became desperate to disclose my story publically. It took several years to arrive at the moment, largely because my wife and I wanted to protect our three children from the fallout of such a disclosure. However, on 8 July 2011, I shared my experience with the world.

Within months, consequences began unfolding at a phenomenal pace – the police were being inundated, investigations ensued, arrests were made. Simultaneously, my family and I were being attacked and ostracised by members of our own community.

It became clear to me that I could not address this issue alone, so the founding of a dedicated organisation in this area became crucial, especially as none existed. Towards the end of 2012 I established Tzedek, a support and advocacy group for Jewish victims of child sexual abuse. The major precursor to this was my written submission and public testimony before the Victoria Government Inquiry into the Handling of Child Abuse by Religious and Other Organisations.

Manny meeting the Dalai Lama in 2007.

Manny meeting the Dalai Lama in 2007.

Coinciding with my founding of Tzedek, former Prime Minister Julia Gillard announced the establishment of the Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse. As information came to light regarding the Commission’s role, I made it my stated mission to ensure that the Yeshivah Centre in Melbourne would be the subject of a public hearing, which is precisely what happened.

There were many successes and positive developments – multiple investigations, arrests and convictions; unprecedented attention from Jewish institutions and the community at large; and, the emergence of an open public dialogue. Nonetheless, my family and I were subjected to ongoing intimidation, including many defamatory statements being made in the online media. The perpetrators of this re-victimisation were predominantly members and supporters of the Yeshivah Centre and Chabad, obviously displeased at the way their institution was being portrayed publically.

It has since been reluctantly acknowledged that the Yeshivah and Chabad leadership, as well as some of its most senior rabbis, were directly implicated in this campaign of intimidation.

While the Chabad response was explicable (if reprehensible), what was truly bewildering was the complicity of the mainstream Jewish leadership. Many were aware of what was going on, yet chose to remain silent. I knew this because in some cases, I had personally informed them. Others must have gathered the facts from the significant media coverage of the issue. In fact, after the Royal Commission hearing,several rabbis contacted me to let me know that they remained silent despite knowing at least some of what was happening. They were the very bystanders they were preaching against, though the traditional context was anti-semitism.

Meanwhile, my family endured ongoing vilification. This became unbearable, catalysing our eventual exile to Europe.

There were many successes and positive developments – multiple investigations, arrests and convictions; unprecedented attention from Jewish institutions and the community at large; and, the emergence of an open public dialogue. Nonetheless, my family and I were subjected to ongoing intimidation, including many defamatory statements being made in the online media. The perpetrators of this re-victimisation were predominantly members and supporters of the Yeshivah Centre and Chabad, obviously displeased at the way their institution was being portrayed publically.

It has since been reluctantly acknowledged that the Yeshivah and Chabad leadership, as well as some of its most senior rabbis, were directly implicated in this campaign of intimidation.

While the Chabad response was explicable (if reprehensible), what was truly bewildering was the complicity of the mainstream Jewish leadership. Many were aware of what was going on, yet chose to remain silent. I knew this because in some cases, I had personally informed them. Others must have gathered the facts from the significant media coverage of the issue. In fact, after the Royal Commission hearing,several rabbis contacted me to let me know that they remained silent despite knowing at least some of what was happening. They were the very bystanders they were preaching against, though the traditional context was anti-semitism.

Meanwhile, my family endured ongoing vilification. This became unbearable, catalysing our eventual exile to Europe.

I was grateful to learn that the Royal Commission would hold a public hearing into Yeshivah. It was our opportunity – the victims, our families and supporters – to share our experiences of the abuse, the cover-ups and the intimidation. The revelations were horrific. It was of little surprise that the public hearing prompted so many resignations, including of the entire Yeshivah Committee of Management and some of their Board of Trustees and Australia’s most senior rabbi, who was implicated directly in the intimidation of my family.

The apologies and resignations are still unfolding at the time of writing. This has provided empowerment and vindication, as has the fact that Yeshivah is now reviewing its entire governance structure.

Europe is a nice change for my family, especially in our temporary home in the Loire Valley, France. But it seems that my heart and mind cannot be distracted from this issue. I am now focusing on a global initiative to address the issue of child sexual abuse within the Jewish community, a monumental task that is proving both challenging and rewarding. I am also still addressing matters relating to Yeshivah, including the civil cases launched by at least thirteen victims as a result of the Royal Commission. And of course, I am still processing the ongoing consequences of my sexual abuse, probably the journey of a lifetime.

If you’d like to learn more about Manny or his work, you can visit his website.

The new ABC documentary Breaking the Silence will be screened later this year.

If this post brings up issues for you around sexual or emotional abuse, please call Bravehearts on 1800 272 831. If you are concerned about the welfare of a child you can get advice from The Child Abuse Prevention hotline on 1800 688 009 or visithttp://www.childabuseprevention.com.au/ or call The Child Abuse Report Line on: 131 478 (Open 24 hours). You can also call Lifeline on 13 11 14.

Originally published at Debrief Daily.

The apologies and resignations are still unfolding at the time of writing. This has provided empowerment and vindication, as has the fact that Yeshivah is now reviewing its entire governance structure.

Europe is a nice change for my family, especially in our temporary home in the Loire Valley, France. But it seems that my heart and mind cannot be distracted from this issue. I am now focusing on a global initiative to address the issue of child sexual abuse within the Jewish community, a monumental task that is proving both challenging and rewarding. I am also still addressing matters relating to Yeshivah, including the civil cases launched by at least thirteen victims as a result of the Royal Commission. And of course, I am still processing the ongoing consequences of my sexual abuse, probably the journey of a lifetime.

If you’d like to learn more about Manny or his work, you can visit his website.

The new ABC documentary Breaking the Silence will be screened later this year.

If this post brings up issues for you around sexual or emotional abuse, please call Bravehearts on 1800 272 831. If you are concerned about the welfare of a child you can get advice from The Child Abuse Prevention hotline on 1800 688 009 or visithttp://www.childabuseprevention.com.au/ or call The Child Abuse Report Line on: 131 478 (Open 24 hours). You can also call Lifeline on 13 11 14.

Originally published at Debrief Daily.